On Thursday

The Old Motor posted to their website

"Mystery Propellor-Driven Car Marysville, Michigan 1932," having come across an old 1932 newsreel showing an odd looking propeller-powered auto that is definitely

not the French Helicron of the same vintage. Well-reasoned speculation as to its origin proved to have been detoured by the misdirection of the Marysville reference however, as the vehicle in question is a product of Detroit. Or rather, the product of one man who lived and worked in Detroit at the time.

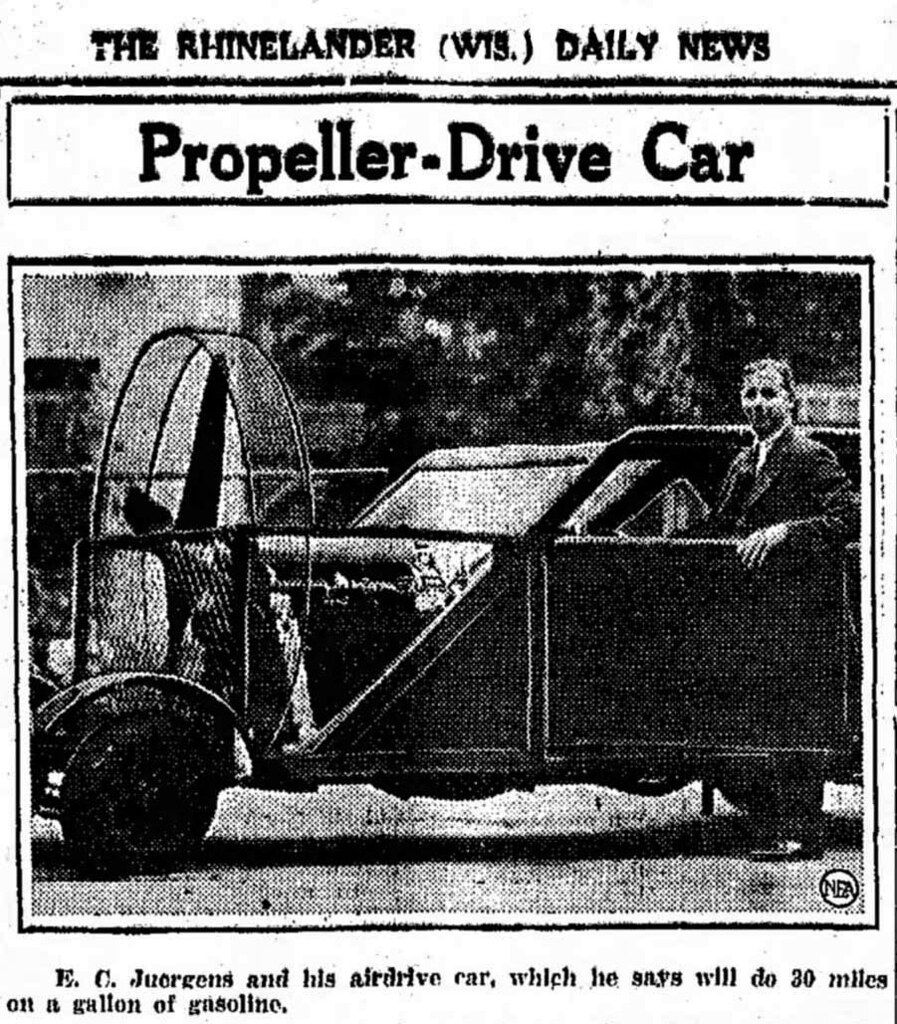

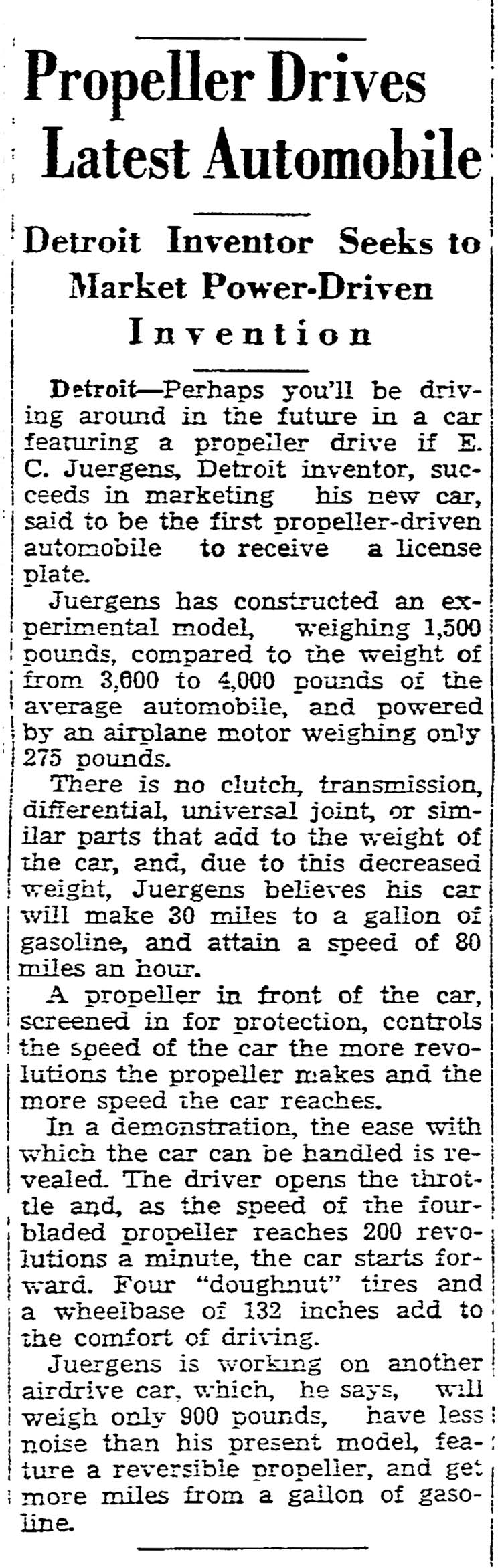

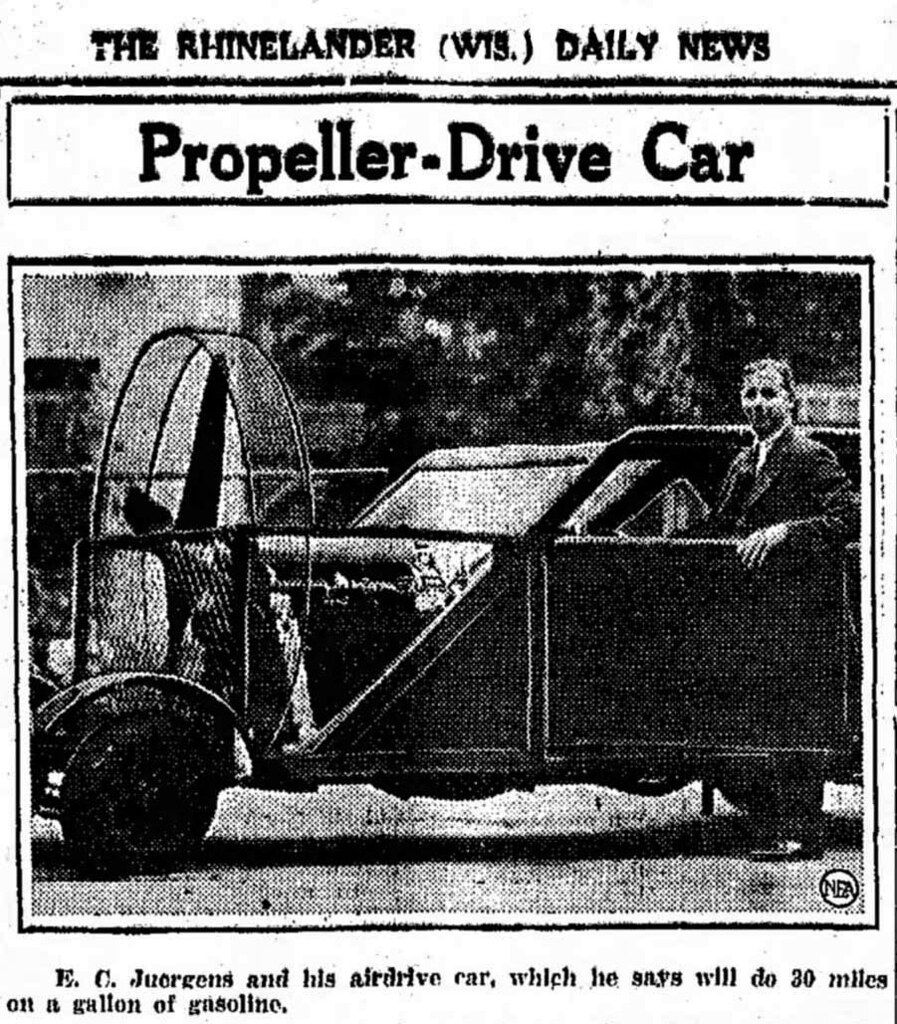

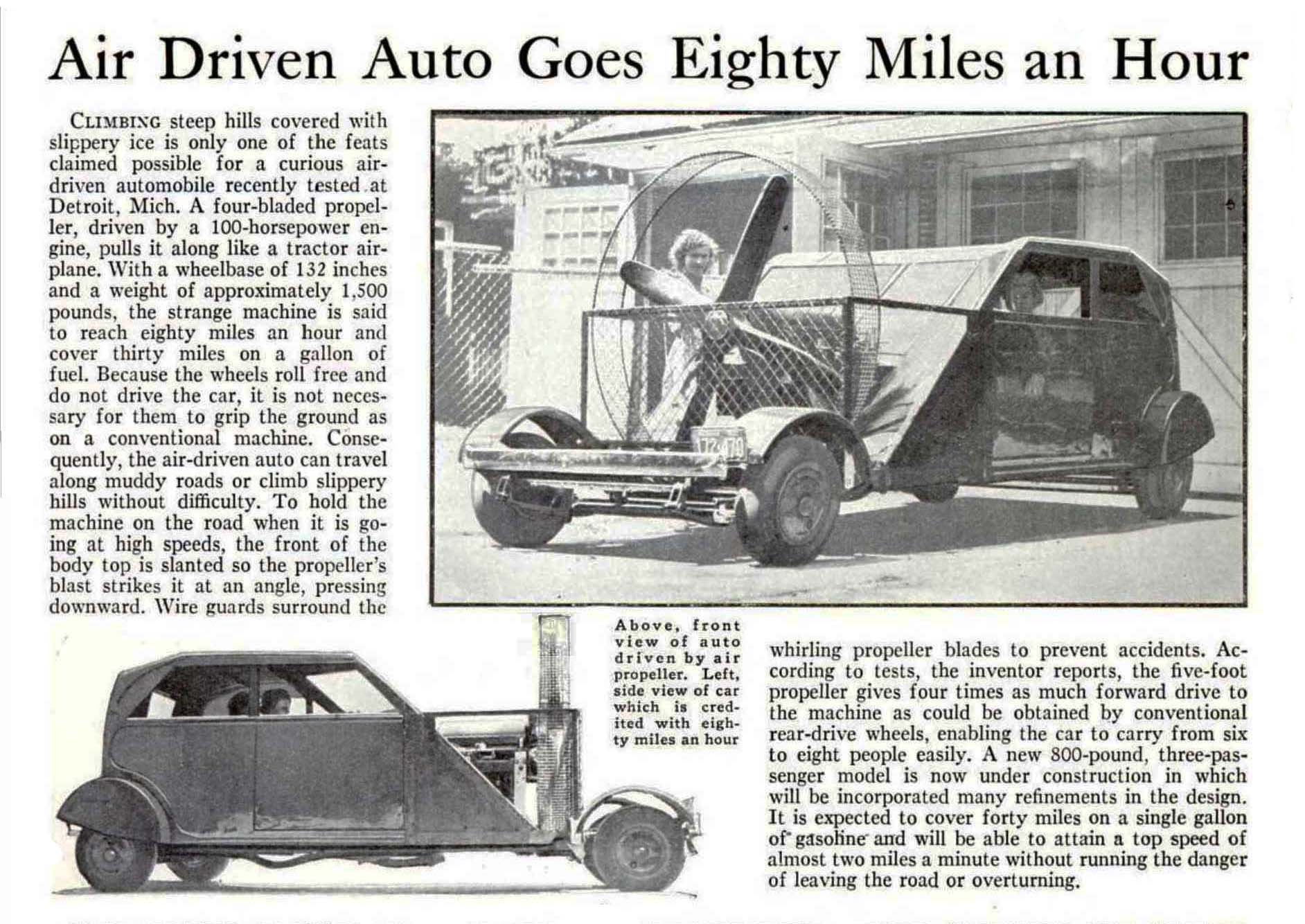

Wire service photograph from the July 22, 1932 edition of The Rhinelander Daily News (Wisconsin)

Wire service photograph from the July 22, 1932 edition of The Rhinelander Daily News (Wisconsin)

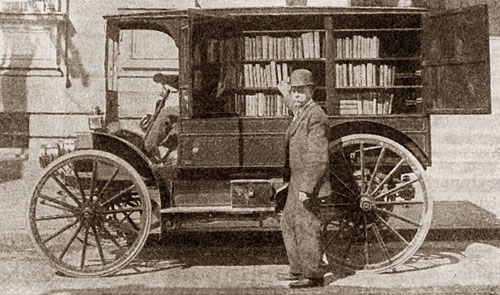

When he was designing his "airdrive" car for himself in the early 1930s, Edwin Columbus Juergens worked as a draftsman for the Ready-Power Company, a Detroit-based operation that manufactured generators that were sold by, among others, International Harvester/McCormick-Deering. However, the term "draftsman" under-defined his talents, as he had previously worked in the auto industry as both a designer and an engineer. In fact, his entire family in America were a talented bunch and deserve a separate post a bit later, just so we can get an idea of where Edwin came from.

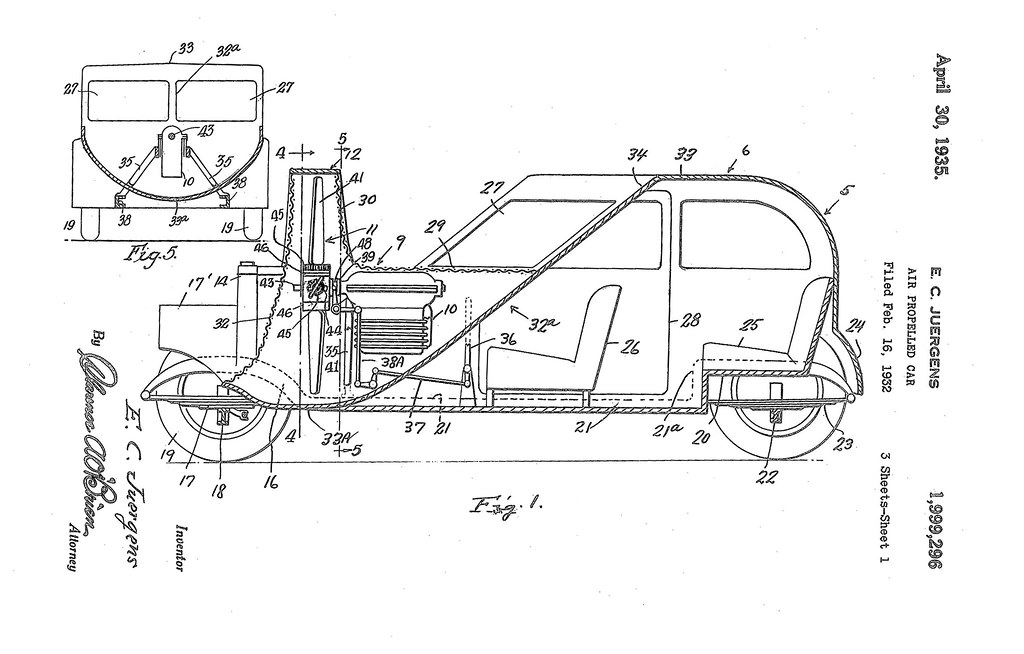

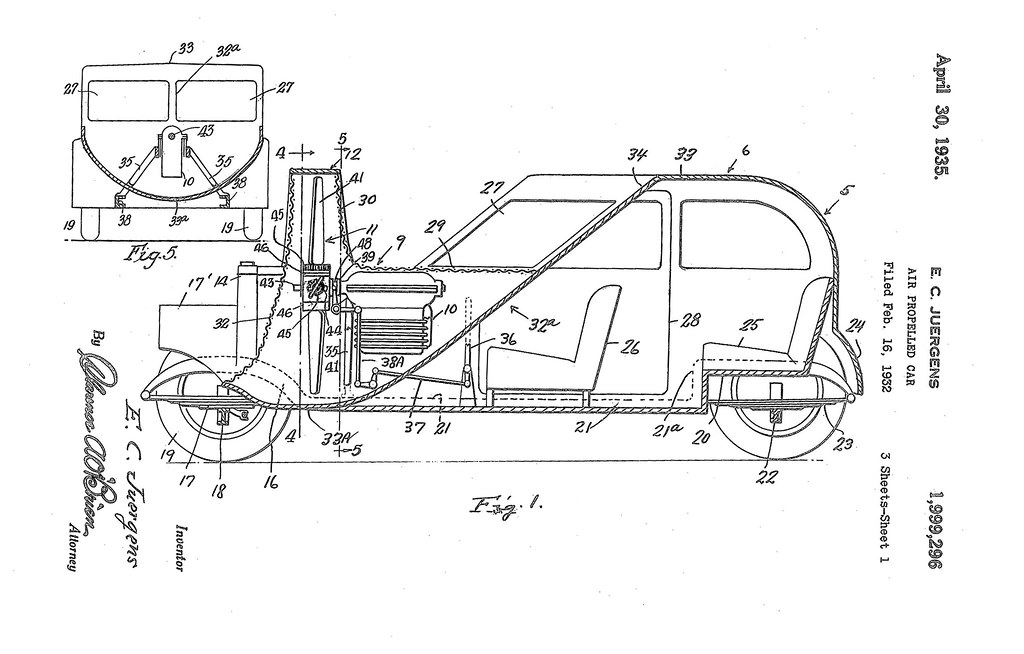

Meanwhile, Juergens applied for a patent on February 16, 1932, and was granted Patent Number 1,999,296 on April 30, 1935

Patent Number 1,999,296, applied for on February 16, 1932, and granted on April 30, 1935

Patent Number 1,999,296, applied for on February 16, 1932, and granted on April 30, 1935

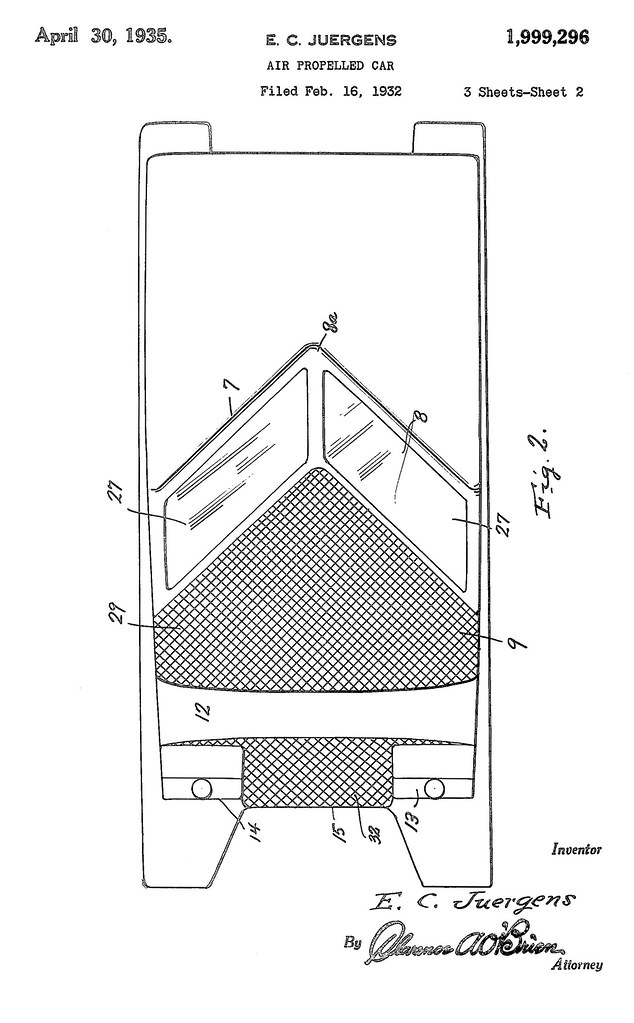

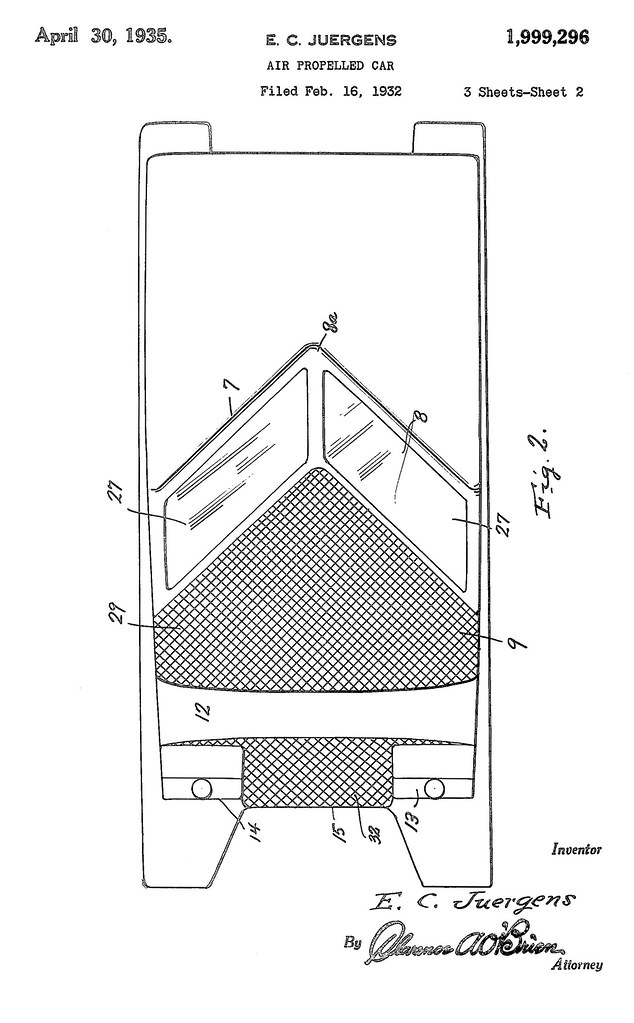

Page 2 of Patent Number 1,999,296

Page 2 of Patent Number 1,999,296

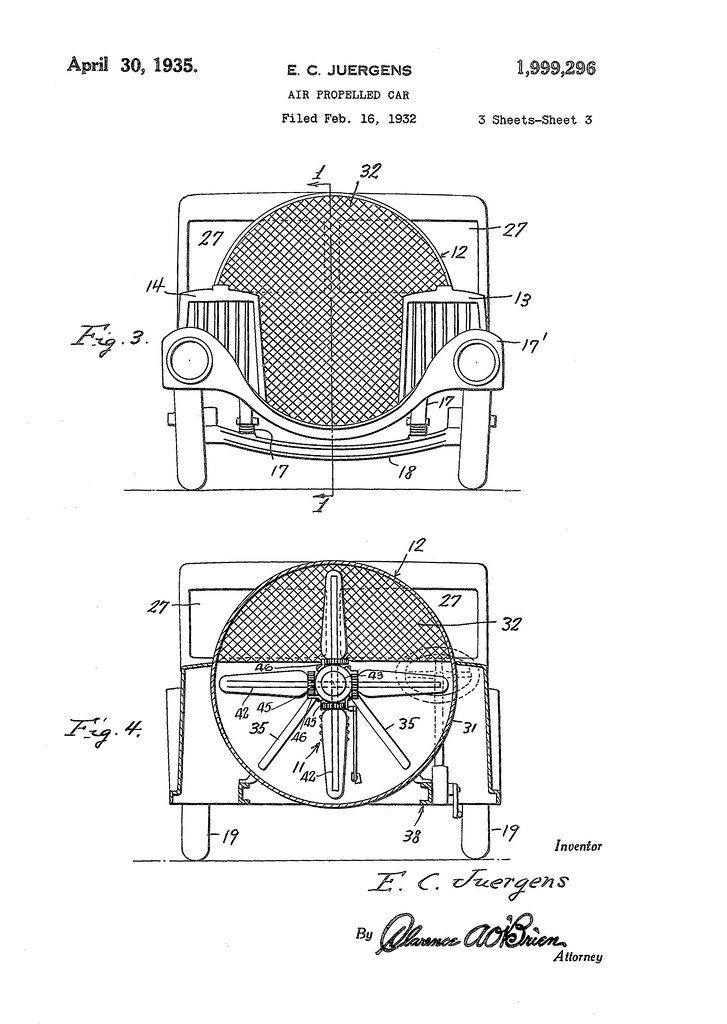

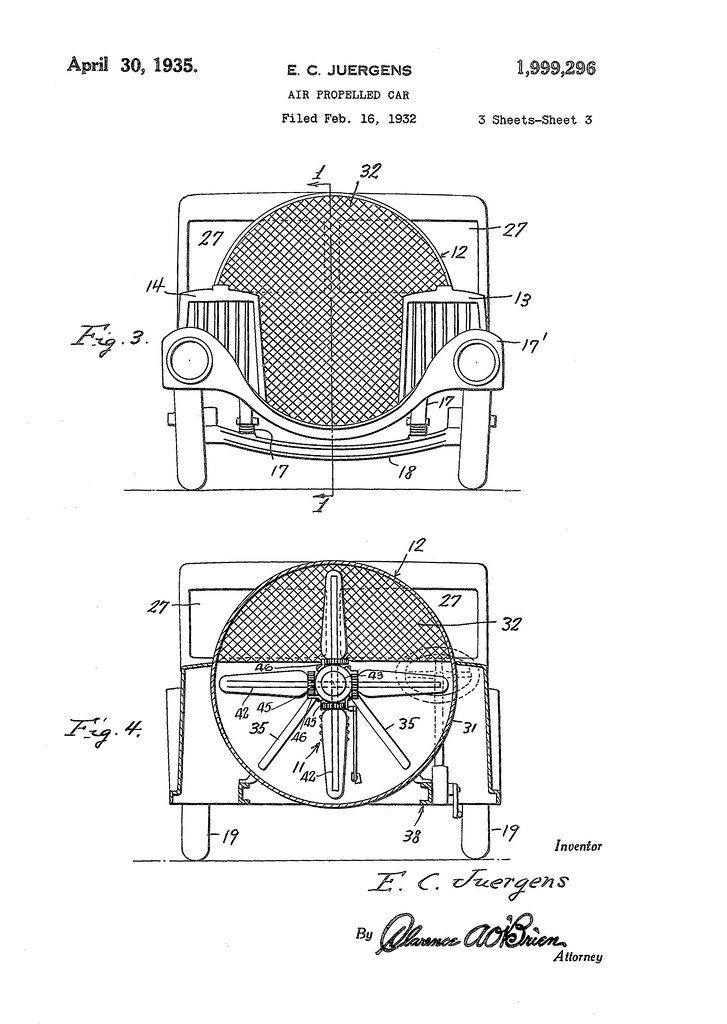

Page 3 of 3 for Patent Number 1,999,296

Page 3 of 3 for Patent Number 1,999,296

The entire patent description (7 pages) can be downloaded

here.

Juergens assigned just over a third (366/1000 to be exact) of the patent ownership to his (presumably) investors: William Goldsmith of Canton, Ohio; David J. Joseph of Cincinnati; and Charles D. Jacobson of Detroit. Goldsmith was Secretary, and later Executive Vice-President of Luntz Iron & Steel Company—his brother-in-law's scrap metal and steel products concern. Joseph was President of the David J. Joseph Company, which also dealt with in iron and steel scrap, as well as new and relay (used) rail. Jacobson was a Vice-President of the David J. Joseph Company, in charge of the Detroit district. Both Joseph and Luntz held offices in the Institute of Scrap Iron and Steel, and both of their respective businesses were among the largest in the country.

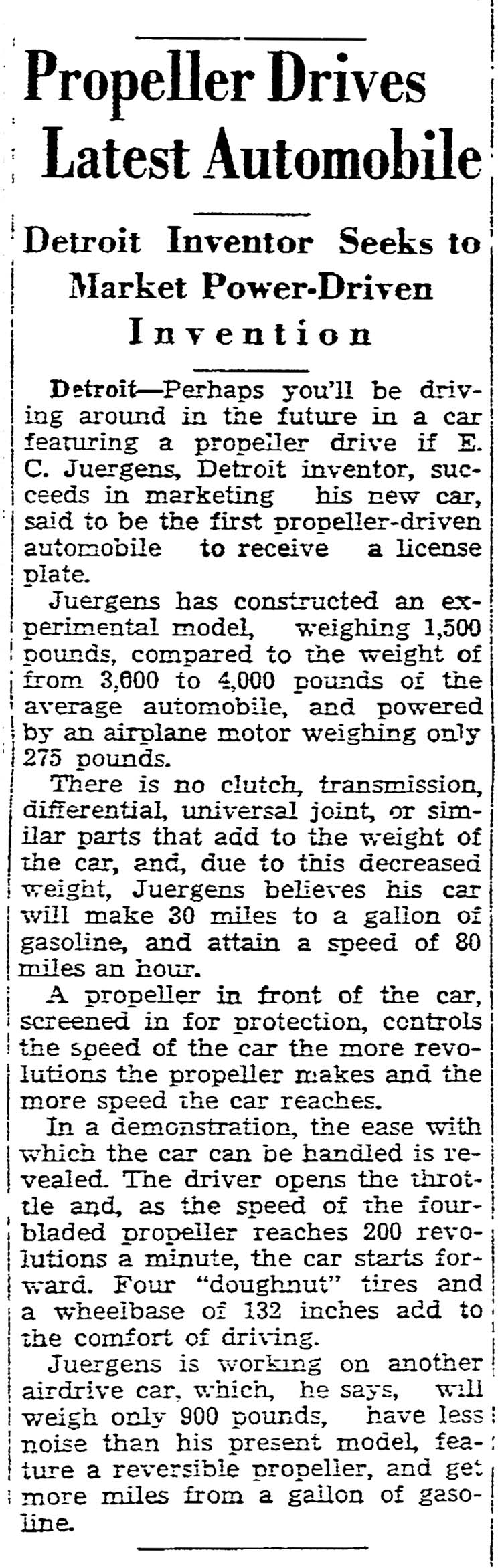

In July and August of 1932, newspapers across the country ran an article supplied by the Newspaper Enterprise Association, Inc. (NEA) news wire service. The often 'edited for length to fit available space' story featured E.C. Juergens and his novel automobile. Headed by titles such as "Propeller-Drive Car" (Rhinelander, Wisconsin), or "Propeller Car May Appear Soon" (Jefferson City, Missouri), or even "Propeller May Be Drive" (Lubbock, Texas—where the heavily truncated story was squeezed in-between "New Fords Going" and "Giant Steer Sold")—and as often as not being published without the photograph—the entire copy was as follows:

Complete NEA news wire article from the August 4, 1932 edition of The Appleton Post-Crescent (Wisconsin), without photograph (as published)

Complete NEA news wire article from the August 4, 1932 edition of The Appleton Post-Crescent (Wisconsin), without photograph (as published)

The newspaper articles attracted the attention of two other major entities:

Universal Newspaper Newsreel (

Universal Newsreel of Universal Studios), and

Popular Science Monthly magazine. The original of the newsreel seen on

The Old Motor, which had sound, is now in the Library of Congress, although a copy can be purchased

here for a mere $350 transfer fee. See Newsreel Highlights of 1932 (UE32097). The

Popular Science article (below), which the

Modern Mechanix website posted way back in March, 2007—years before anyone else picked up on it—can be read online in the original December, 1932 issue

here (page 49).

Cover of the December 1932 issue of Popular Science Monthly magazine featuring the Juergens Air Propelled Car

Cover of the December 1932 issue of Popular Science Monthly magazine featuring the Juergens Air Propelled Car

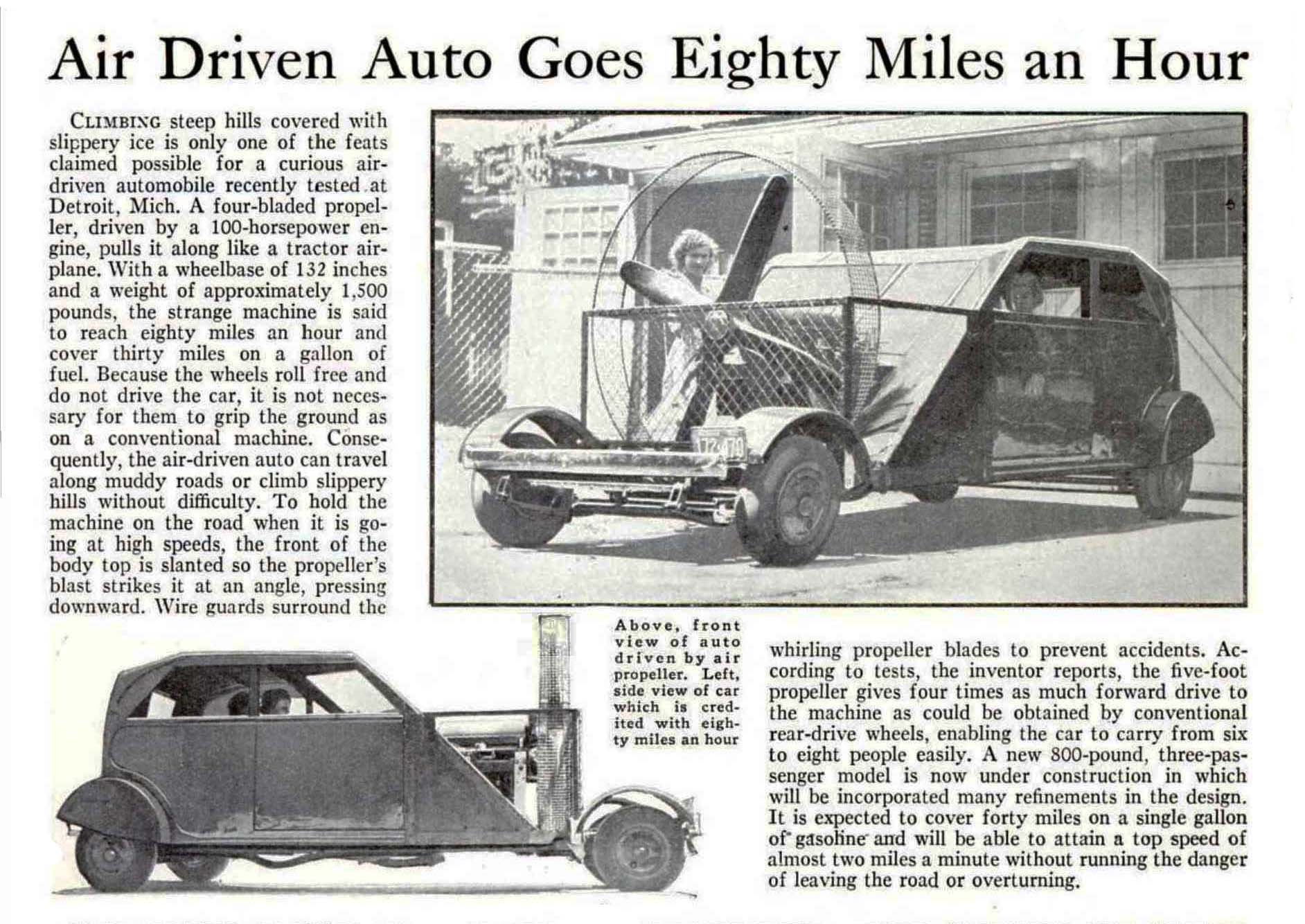

Juergens Air Propelled Car article featured on page 49 of the December 1932 issue of Popular Science Monthly magazine

Juergens Air Propelled Car article featured on page 49 of the December 1932 issue of Popular Science Monthly magazine

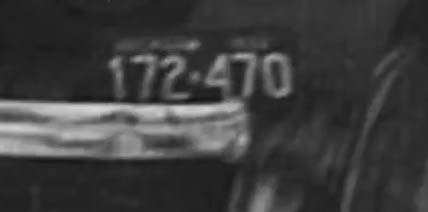

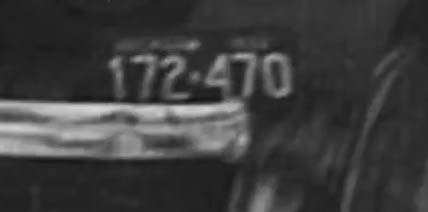

The news wire copy noted the air-drive car was "...said to be the first propeller-driven automobile to receive a license plate." Whether or not it was the first, it most certainly was licensed for the road as evidenced by the plate photographed in the article and rendered on the front cover art of the magazine (above). A screen grab taken from the video on

The Old Motor site provides a little clearer picture of the 1932 Michigan license plate.

Screen shot of the license plate taken from the Critical Past copy of the Universal Newsreel featuring the Juergens Air Propelled Car

Screen shot of the license plate taken from the Critical Past copy of the Universal Newsreel featuring the Juergens Air Propelled Car

The pictures and the newspaper and magazine articles describe a 6-to-8 seat air-drive car weighing in at a light 1,500 pounds on a 132-inch wheelbase, with a 275-pound, 100-hp airplane engine powering a five-foot, four-bladed prop that would start to move the car at 200-rpm. It also sported a unique wedge shape that took advantage of the prop wash to act as a down-force. The fuel mileage and top speed hadn't yet been tested at press time, but was estimated by Juergens as 30-mpg and 80-mph respectively. What the car did

not have was a clutch, transmission, differential, live rear axle, or any u-joints.

Features provided for in the patent that did not make it into the prototype included: Twin radiators (Items 13 and 14 on Figure 3, Page 3 above) for a water cooled engine, if fitted; the V-shaped windshield (Page 2 above), or—possibly the most important item— a reversible prop. This last item would be controlled by a single hand lever that would allow the operator to use the prop to slow down, stop, and even reverse the vehicle. According to the patent description, feathering the prop would stand in as a clutch, and adjusting the pitch of the prop blades would allow "...for attaining different speeds with varying loads, and at varying engine speeds, so as to obtain the maximum speed and pulling power and provide for operating the car with the maximum economy of fuel."

All-in-all there 18 specific claims in the patent—all unique enough for the patent to be approved. Many of the patent features were to be employed in a lighter 3-place car, maybe weighing around 800 to 900 pounds, but still using an air-cooled aircraft engine. Juergens figured that the lighter version would get around 40-mpg and top out at just under 120-mph. It may be that we are destined to never know, since there seems to be no evidence that the second prototype was ever built. Still, it appears that, as far as actual usage is concerned, the Juergens Air Propelled Car proved to be one of the more successful builds. Edwin did indeed put more than a few demonstration miles on it. If the video over at

The Old Motor is to be taken at face value, then the car made a roughly 100 mile round-trip to Marysville—where it was filmed by

Universal Newsreel—and back. But before that, Juergens preformed a reliability run of his own devising. He made a 200 mile round-trip to Fremont, Ohio—his wife's home town—creating "no little interest." It was a nostalgic homecoming, the reason becoming clear in the next post about the life of Edwin Columbus Juergens.

Not much more was ever heard about the Juergens Air Propelled Car, except for being referenced in five other patents concerning cars driven by propellers. One such

creation went Juergens one (or perhaps four) better by driving all four wheels using gearing off the prop. For other brave and some perhaps no-so-smart attempts at building propeller-driven cars, see

here,

here, and

here. There is some repetition, but each has a few that are unique to that site. And then there is this

candy clown—claiming to be first in 1955!

Next post: The life and family of Edwin Columbus Juergens