Updated 12/09/2019*

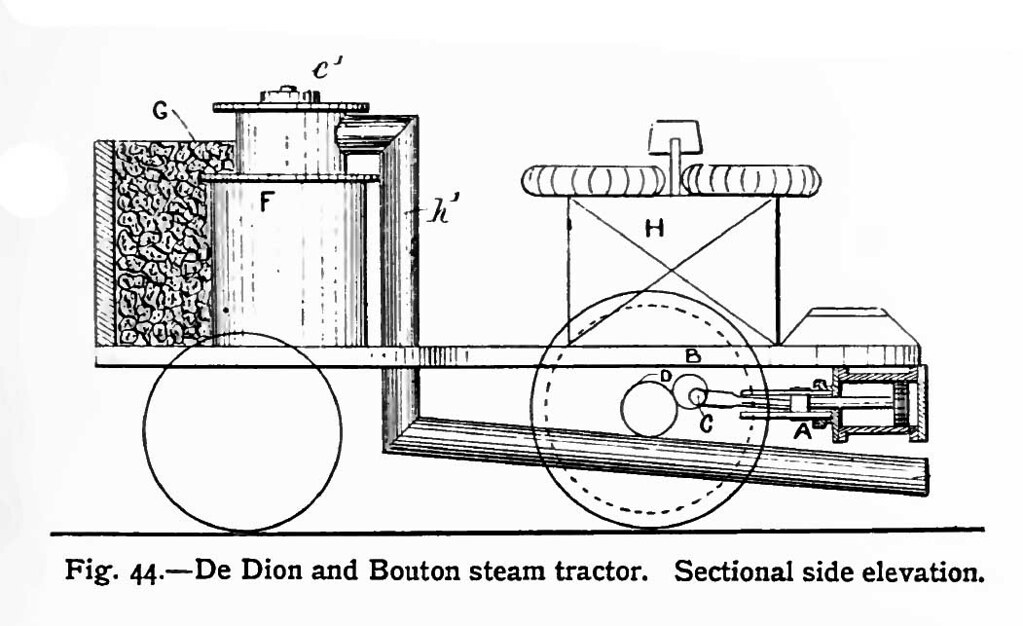

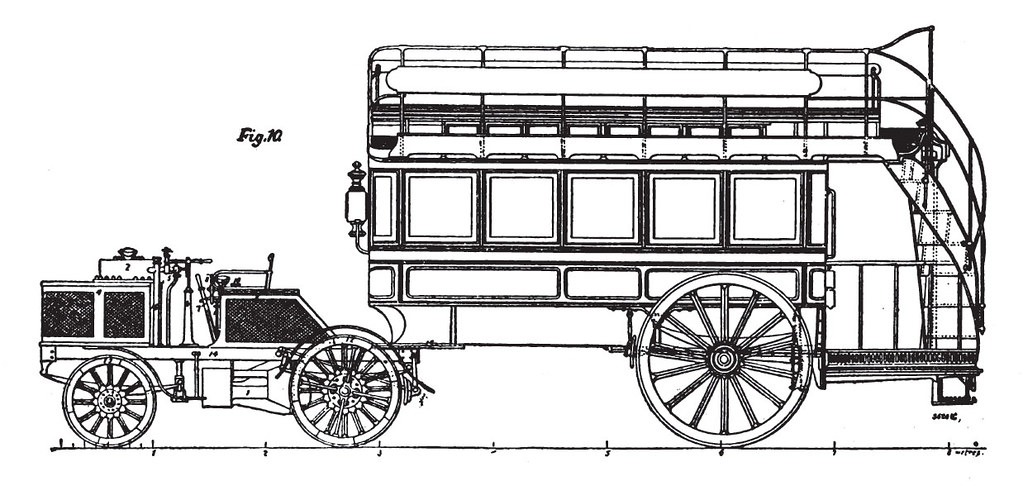

While researching the material for the De Dion segment of the Land Tug series, I found numerous mentions to "the very first auto race." Often the source would then mention an earlier race. Well, if there was an earlier race, wouldn't

that one be the first? As we will see, no. But as it turns out, the first still wasn't the first either, so let's look at race claims, counter-claims, and the perils of internet research.

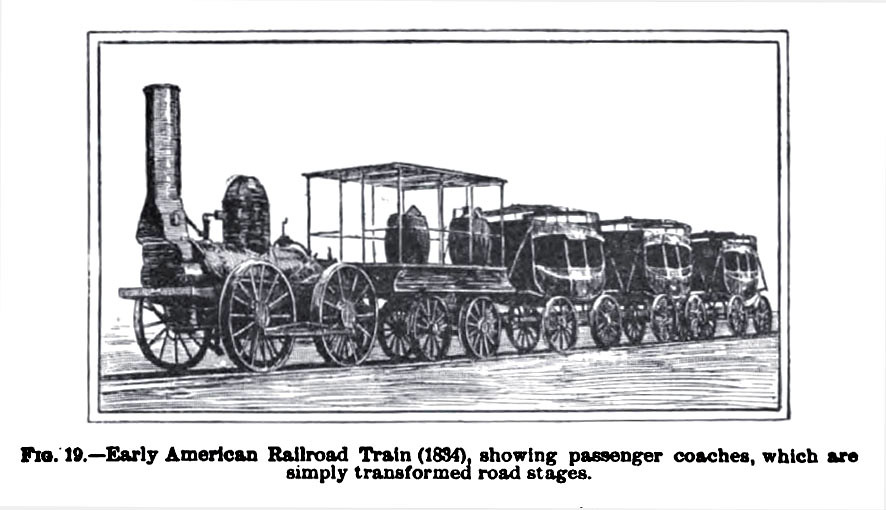

Just this summer many of us learned that what we thought was the first ever auto race, turned out to be the second (or third) by about 16 years or so. Daniel Strohl of Hemmings Blog fame has written an excellent

summary of the Great Green Bay-to-Madison Steam Wagon Race of 1878, while the website for the

Wisconsin Historical Society relates how the story was "rediscovered." The original essay by Wisconsin Secretary of State John S. Donald appeared in the October, 1916 issue of

The Wisconsin Engineer.

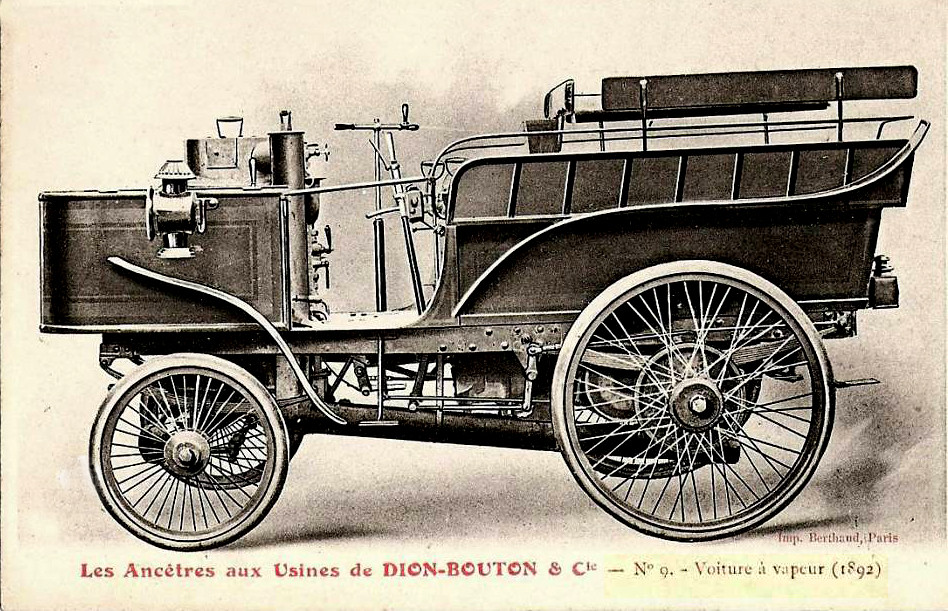

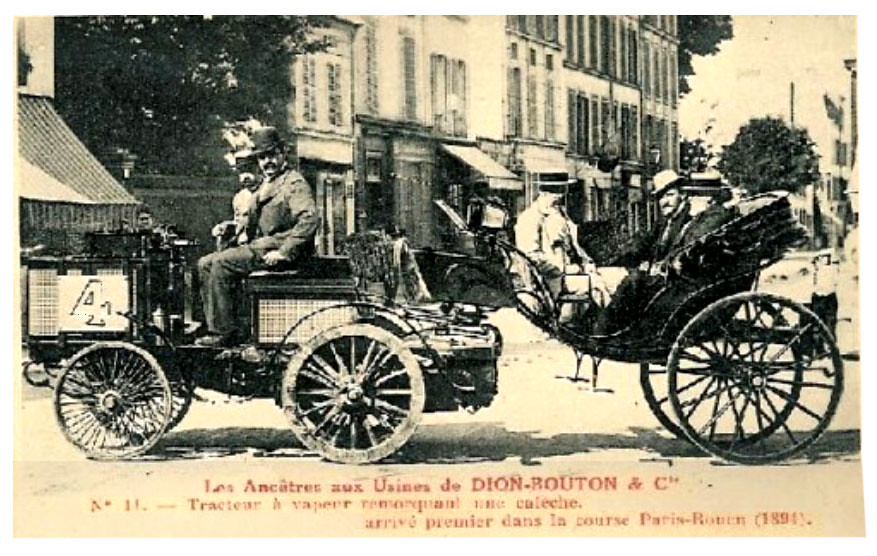

Most histories state that the

Le Petit Journal sponsored Paris-to-Rouen race in France on July 22, 1894 was the very first. Given the Steam Wagon Race of 1878, it would properly be the second. However, there had been an earlier race of sorts in 1887, but the information available on the internet is woefully lacking. If you Google "first auto race" you will eventually come across a reference to the April 28, 1887 race sponsored by the magazine

Le Vélocipède and its editor, a certain Monsieur 'Fossier.' Google "'Le Vélocipède' Fossier" and you will get over 6,800 entries that all state something very much along the lines of:

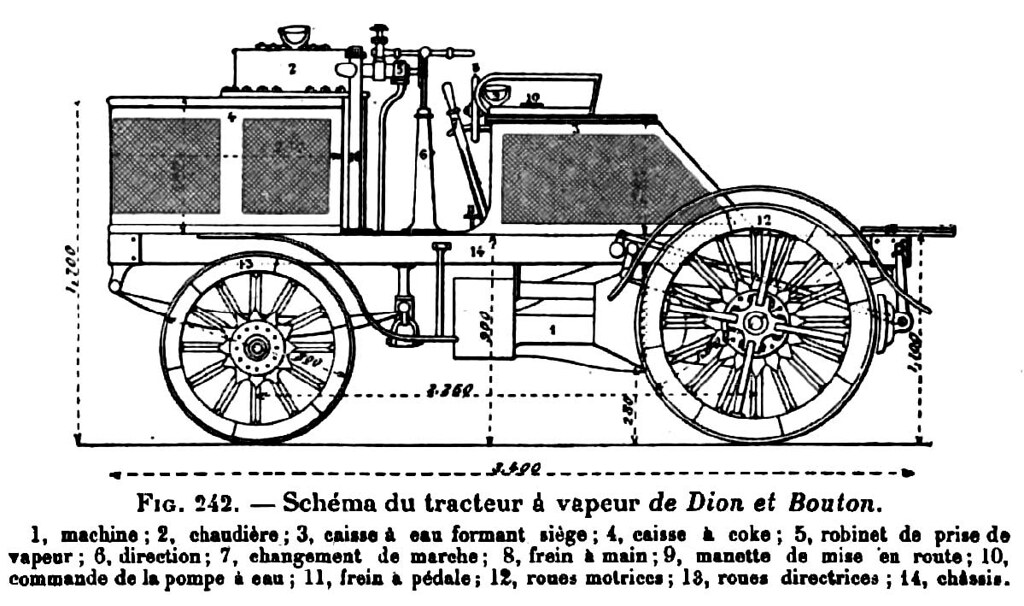

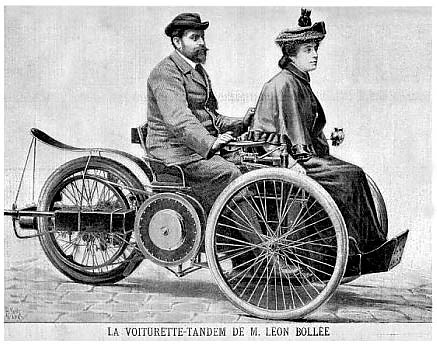

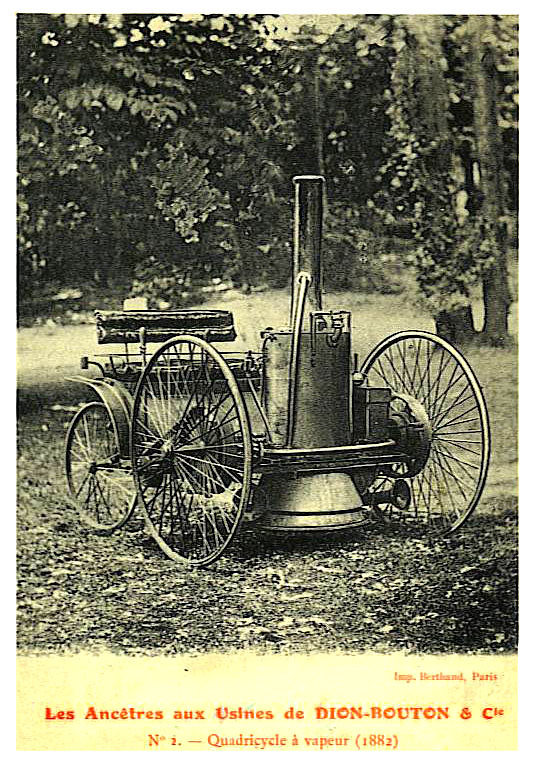

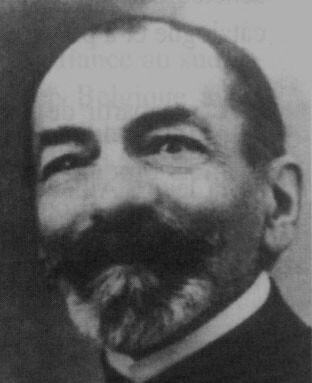

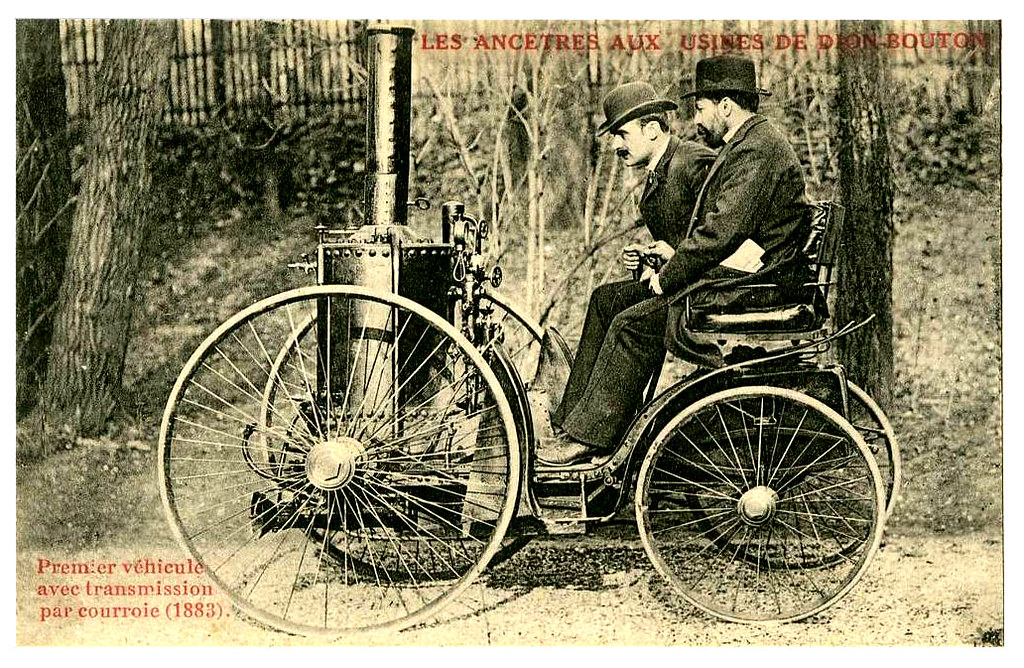

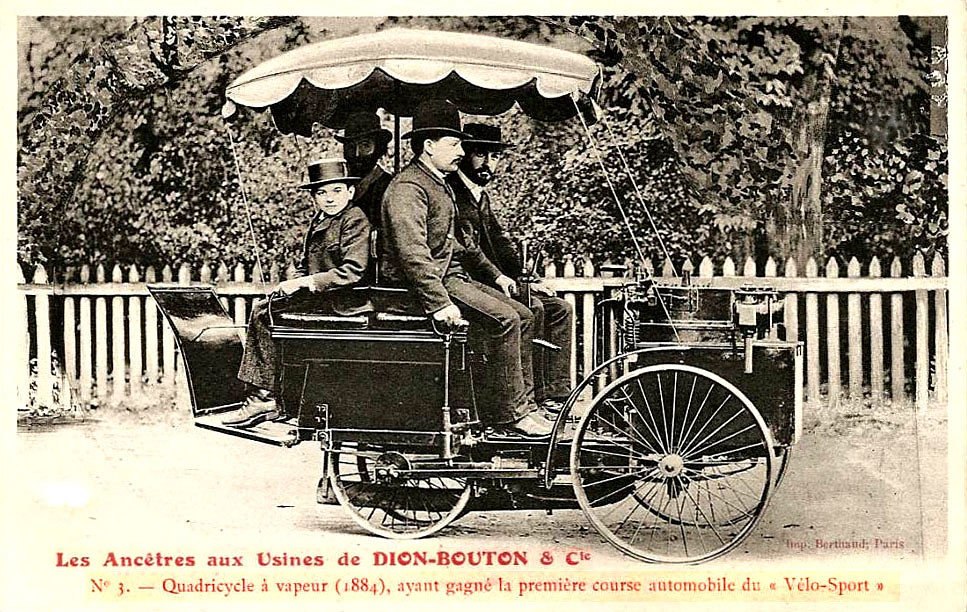

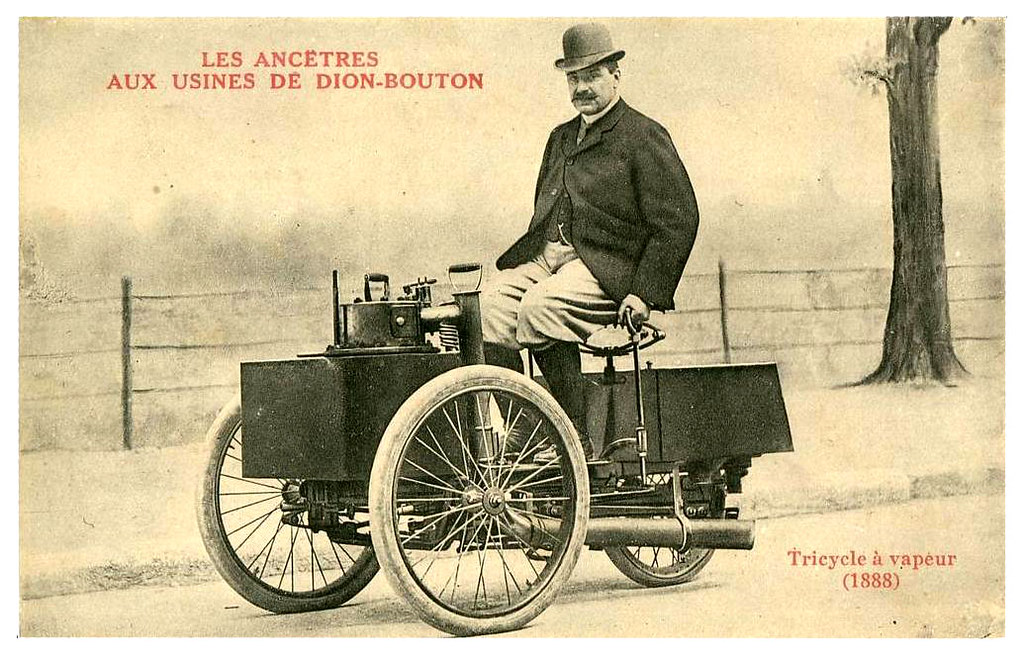

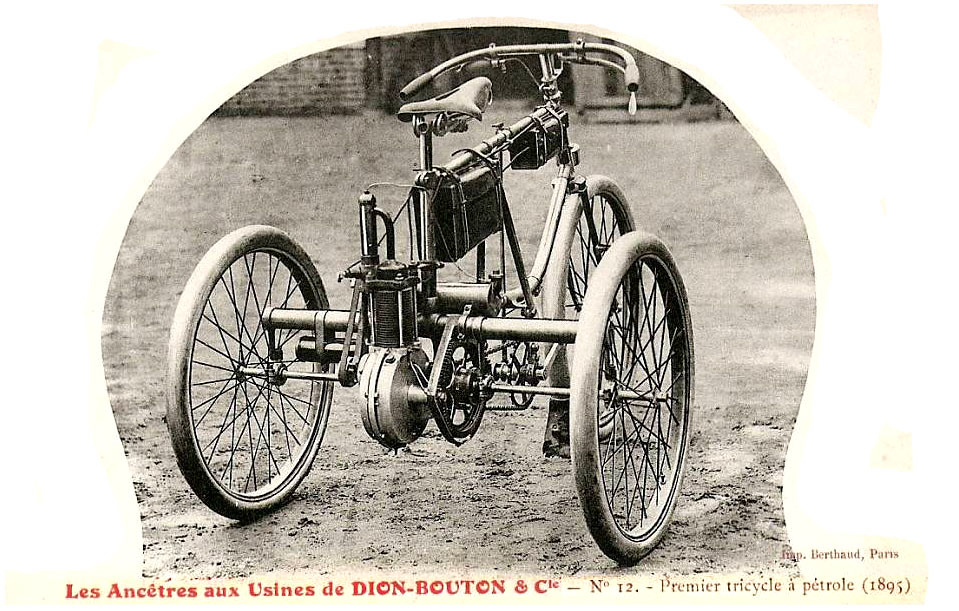

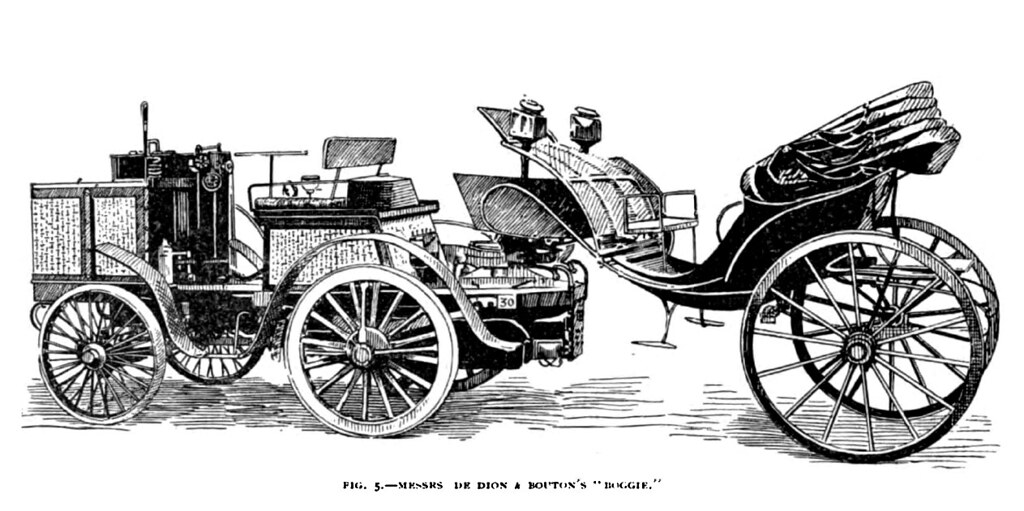

The first race ever organized was on April 28, 1887 by the chief editor of Paris publication Le Vélocipède, Monsieur Fossier. It ran 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from Neuilly Bridge to the Bois de Boulogne. It was won by Georges Bouton of the De Dion-Bouton Company, in a car he had constructed with Albert, the Comte de Dion, but as he was the only competitor to show up it is rather difficult to call it a race.

As it turns out, they are all copying a

Wikipedia entry almost to the letter. And that is my pet peeve - website after website blindly copying and pasting erroneous information, and thus making the incorrect story the new truth. See the

Locomobile entry for another example.

In turn, Wikipedia cites a May 28, 2003 entry by Rémi Paolozzi on the Autosport.com 8W forum. (8W stands for

Who? What? Where? When? Why? on the World Wide Web - The stories behind auto racing facts and fiction.) There Paolozzi takes 1 (out of 10) paragraph to tell the story - without citation - that Wikipedia condensed down to a few lines that thousands would copy without citation.

Caveat - never, ever trust what you read on Wikipedia. Using it as a starting point for research is fine, but try to trace anything you read back to the primary source. So far I haven't found any earlier examples of the story than this...in English.

The big problem here is that when you read the English Wiki entry for

Le Vélocipède, you find that it is properly titled

Le Vélocipède Illustré, and that Richard Lesclide was its editor, and that it folded in 1872 - some 15 years before the race. No amount of tweaking search parameters reconciled the disparity. At least, until I switched to Google.fr - the French version. Then the clouds parted and the sun shown down upon my darkened disposition. And no, I don't speak/read/write French, but I can fling Google Translator around with the best of them.

First, there is no Monsieur Fossier. There is, however, according to the French version of the Wikipedia entry for

Le Vélocipède Illustré, a Paul

Faussier who was a sports journalist, a ranked cycle racer, and a member of the Metropolitan Vélocipédique Company. And he did indeed organize what was supposed to be the first horseless carriage race between Neuilly and Versailles on April 28, 1887. [Source -

Les Défricheurs de la Presse Sportive (

The Pioneers of the Sports Press) by Jacques Marchand, Atlantica, 1999.] As for the discrepancy concerning the demise of the journal

Le Vélocipède Illustré - it turns out that the magazine had a second life.

According to the French Wikipedia site, Richard Lesclide launched the first issue of the journal in Paris on April 1, 1869 as an illustrated bimonthly specializing in the new sport of cycling. Lesclide was a pioneer of sports journalism who would one day be secretary to Victor Hugo.

Le Vélocipède Illustré organized the first city-to-city cycle race in history on November 7, 1869, between Paris and Rouen, which would be the same route used 25 years later for the first real auto race in Europe. As noted above, the magazine folded in 1872, but was resurrected in 1890 by the now 67 year-old Lesclide. After he died in 1892, his wife Juana acted as editor under the

nom de plume Jean de Champeaux. Sometime later Paul Faussier took over as editor and apparently continued until the journal folded for good around 1901. So Faussier (and not Fossier) was indeed the editor of

Le Vélocipède Illustré, but not during the the time of the 1887 auto non-race - which he did indeed organize. [Source -

Les Premiers Temps des Véloce-Clubs: Apparition et Diffusion du Cyclisme Associatif Français Entre 1867 et 1914 (

The Early Days of Swift-Clubs: Emergence and Spread of French Cycling Associations Between 1867 and 1914) by Alex Poyer, L'Harmattan, 2003.]

So what does all of this mean? Simply that, until someone's future research uncovers an earlier event, the record stands thusly: The first

documented self-propelled auto race in the world took place in Wisconsin in 1878 (two entries/one finisher). The 1887 event that some claim is the first race was not a race (one entry/one finisher). What was thought to be the world's first race was actually the world's second, but still Europe's first (multiple entries/multiple finishers). What was thought to be the first American auto race in November, 1895 (multiple entries/multiple finishers) was actually the second American race - 17 years after the Wisconsin race of July, 1878.

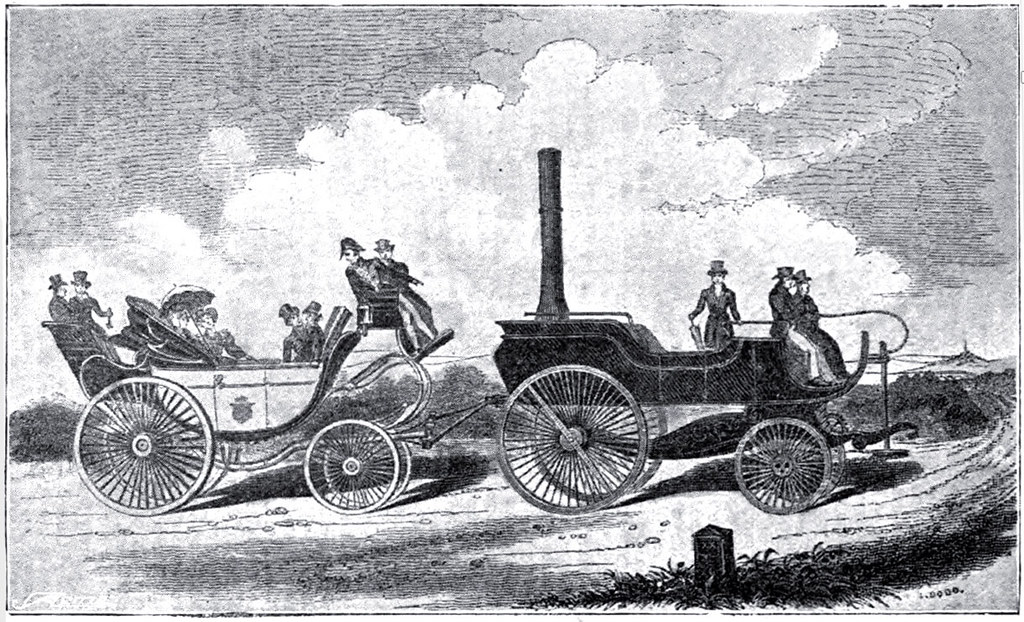

Given the early flurry of steam propulsion activity in England (see previous post) I'm betting that if any evidence surfaces for an earlier race, it will be there.

*Hemmings

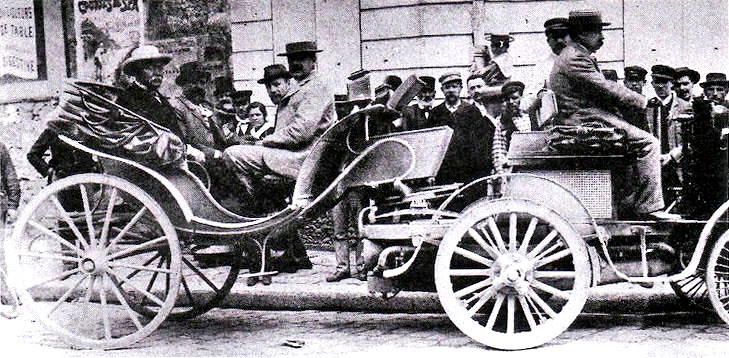

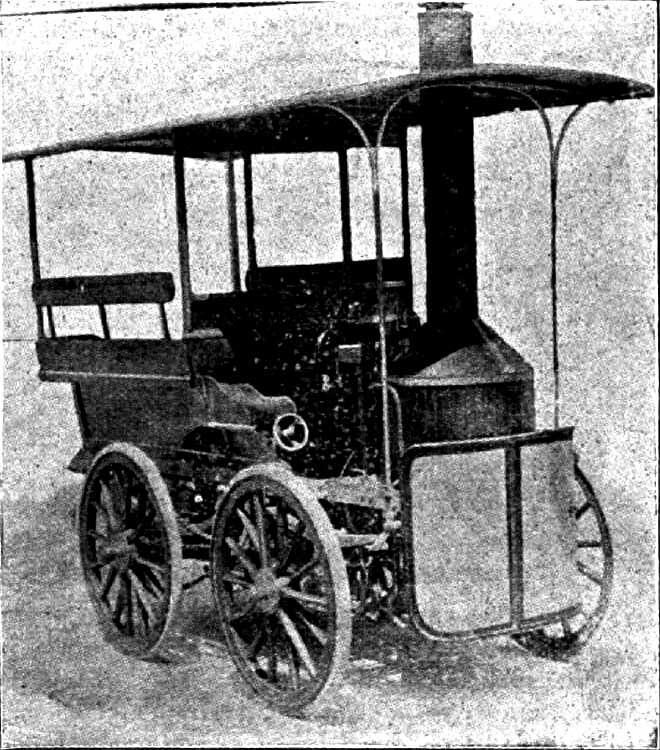

notes (scroll down) that "one of the selling points for “La Marquise,” the world’s oldest operating vehicle, was the claim that it participated in the world’s first automobile race, though...that claim is dubious, considering that the race took place many years after the 1878 Wisconsin steam buggy race we wrote about back in June."

Considering that the 1887 event was only had one entry, it was more properly a time-trial, rather than a race. That makes the claim that the “La Marquise” participated in the world's first automobile race

doubly dubious. That said, if the new owner feels cheated and no longer interested in the vehicle, I'd graciously accept it as a lovely parting gift.